ENGLISH

A Conversation with

Rossella Schillaci

Tra le macerie e le miserie lasciate dalla dittatura e dalla guerra,

non si aggirava un fantasma, ma una forte voglia di ricominciare

(Graziella Falcone, in Fondazione Nilde Iotti)

Silvia Raimondi, Johns Hopkins University

Rossella Schillaci was born in Turin, where she has filmed several of her documentaries. After graduating from university and attending Daniele Segre’s Scuola Video di Documentazione Sociale, she pursued a Master’s in Visual Anthropology in Manchester (UK). It was there that she learned to represent reality using images rather than words. Thanks to that experience, and to her encounters with the experimental filmmakers Jean Rouch and David MacDougall, she turned her attention to themes of resilience and what it means to be human.

Rossella Schillaci’s documentaries deal with the topics of immigration and incarceration. Her documentaries are the product of personal encounters and address anthropological questions surrounding the daily challenges that men and women face, and how these individuals are transformed and empowered.

In Altra Europa (as well as in Solo questo mare and Shukri, A New Life), the sea and, at the same time, the city form the background. The refugees featured in the films have just arrived in Italy and their difficulties and trials are shown through a narrative constructed by the use of interviews, images, and sounds. Schillaci’s preferred technique centers on human encounters, relationships, and the foundation of those relationships. This technique pulls the viewer directly into the situations which the director reflects upon and investigates. An example of this is Ninna Nanna Prigioniera (2016), a documentary which centers on the mother-child relationship between an incarcerated mother and her child. The viewer is brought into close contact with prison life with the aid of interviews with the children’s teachers and the mother. Most importantly, the viewer can identify with what the child experiences as the camera is brought down to the point of view of the child

Among Schillaci’s works, which feature human resilience as a central theme, is Libere (2017) - a documentary on the Italian Resistance. It is unique from the filmmaker’s other works in that there is no direct encounter with the individuals involved; instead, Schillaci tells the story by exploring historical archives such as the Archivio Nazionale Cinematografico della Resistenza in Turin. The film provides an insight into the perspective of the ordinary women and young girls who worked in the Resistance. The work features recollections of the past and traces Italy’s course to freedom alongside a story of female emancipation. It presents women, not as heroes, but as ordinary individuals capable of “taking extremely courageous decisions, facing extraordinary times, risks and challenges.”

Silvia- Your background and studies are linked to the “Scuola Video di Documentazione Sociale” and your subsequent work as a filmmaker has followed the same path. Could you explain the reasons for your choice? And how did you become a documentary filmmaker?

Rossella- I became a documentary filmmaker by chance in a certain sense, even though my studies are partly the reason. In college, I studied both cinema and anthropology, and my mentor at the time introduced me to visual anthropology – a field I did not know much of before as it is not one commonly studied here in Italy. This is how it all started: I began by studying cinema and anthropology at university, then went on to Segre’s film school in Turin, where I combined the theoretical aspects I’d learned at university with hands-on experience. Segre’s school gave me my technical skills—I learned how to use cameras, lighting, audio equipment, and how to edit the film. I also mastered practical methodology, which means developing an idea and working it through to the end result. Having completed my thesis on Visual Anthropology, I heard of a Master’s course in Manchester entirely dedicated to Visual Anthropology.

S- Did that Master’s program lead you to approach documentary filmmaking from a different perspective? Did it perhaps enable you to address certain topics with greater attention to humanity and human rights? Is your choice to examine marginalization connected to this background?

R- Definitely, but at the same time, my choice was the outcome of my past studies alongside my passion for photography. I owned a video camera and developed my own photos in a dark room, and it was this visual aspect that I loved and fascinated me the most. And then I discovered the documentary format, thanks to the film festivals I went to, like the one in Turin and the “Festival delle Donne” (Women Film Festival). At these festivals, I watched numerous beautiful documentaries and got to discuss them with the women filmmakers who, like me, had similar backgrounds in anthropology. Then, the master’s degree in England was fundamental. In fact, if at Segre’s school I’d learned storytelling using the spoken language of interviews, in Manchester, I learned to describe reality through “participant observation,” using images, not merely words. I also learned the anthropological method of field research that showed me how important it is, and how necessary, when making a good documentary, to build collaborative relationships with the people you want to work with. These relationships need to be based on trust and sharing. Moreover, the master’s degree gave me the opportunity to analyze the work of Jean Rouch and David MacDougall, both of whom I have always greatly admired. For me, they were among the most significant filmmakers because they combined solid competences in anthropology with excellent filmmaking. In their work, they show that there is no one single way to create a documentary, but that it can take different forms, depending on the subject and the topic that you are dealing with.

Regarding your second question, I think that at the core of my work there is always an encounter with reality, with people who spur me on to ask a series of questions, both anthropological and personal. For this reason, I’ve often changed topics, consistently exploring very difficult and challenging situations: from imprisonment to migration. What I’ve always found very interesting is young men and women in situations that are completely outside my own realm of experience. For me, these contain precious life lessons. Above all, the things that most interest me are the resilience strategies that human beings use, so I would not define the protagonists of my documentaries as marginalized. In fact, I’m less interested in marginalization than in its opposite: the challenges, trials and tribulations that young people face, and the consequent changes and transformations that society imposes on them. Indeed, take how our society reacts to the arrival of migrants, to the problems and difficulties that they create. This is what I reflect on in my work and what I want to highlight. Rather than terming it ‘marginalization,’ I prefer the term ‘transformation:’ empowerment, whether personal or collective.

Figure 1- Ghetto PSA (2016), a short film produced by Unafilm and Azul

S- So, for example, I’m thinking of the moment in Altra Europa (2011) when some Turin residents are worried about the impending transfer of refugees to their neighborhood. Was that why you included it, to show how our culture reacts to immigration?

R- Yes, absolutely. But I need to tell you more about this project and the others I’ve done on immigration (Solo questo mare -2009-; Shukri, a new life - 2010). For various work reasons, in 2005 and 2006 I got to interview the Sicilian Coast Guard. They told me about sea rescues they performed and, as it was a less-known topic, I felt I needed to go deeper and look at immigration from the Coast Guard’s point of view. The project then became more structured because, when I went back to Turin, I discovered that a former clinic in my neighborhood was now accommodating the very same Somalis that had been rescued by the Coast Guard. Then, when one of my colleagues, the photographer Chiara Ceolin, started gathering material for a photo-journalism reportage on the same topic, I was able to go with her. It was an important moment because, with her, I was able to conduct the interviews and explore the situations I wanted to describe. In fact, until then, I’d only recorded the Coast Guard’s point of view but was missing the other side of the story. And it was there that I learned about the terrible journey refugees had to make – I don’t need to go into it here because today I think we all know about it now. I noticed how these very young people tell you about their tragic experiences laughing, with an incredible irony that makes you wonder, “Would I be able to do the same?” or “How come we don’t know about these things?”. Using Chiara Ceolin’s photos, we staged an exhibition and screened a short film that contained the interviews and recordings that I’d made. The short film, edited by Fulvio Montano (Approdi/Landing, 2006), received good feedback, and from this the idea of a bigger project was born. So, next we made Solo questo mare. In the beginning, it was only to have been a trailer to raise funds, but then it evolved into a different project. We met an Al Jazeera commissioning editor who asked for a 20-minute documentary about the perspective of a young woman, Shukri—describing her life at the refugee center and her search for a job—to get an insight into how these people adapt to their new life in Italy. So, we made Shukri - a new life for Al Jazeera, and simultaneously, we went forward with Altra Europa. There’s a degree of crossover between these projects, actually. They were birthed from the same situation and feature the same material, but at the same time they’re different in terms of how the material is used. These projects show us that the immigration situation is still regarded as an emergency in our country, despite the fact that the dynamics have been the same for twenty years – yes, twenty. By continuing to classify it as an emergency, politicians and government officials can avoid making decisions. In fact, constantly describing it as an ‘invasion’ and ‘emergency’ means they can present it to the public as dangerous and to make less democratic decisions. This makes it a very interesting topic to explore and discuss.

S- Did you encounter any problems during this project? I imagine that the cultural issues and cultural differences must have impacted you personally. Can you tell me what it was like trying to create relationships with people so culturally different from Italians?

R- Yes, there were many difficulties; in fact Altra Europa took us several years to complete. The only rules we set ourselves were to be patient in our work, not rush our preparations, and build relationships of trust with the people we wanted to interview. In the beginning, we just had a photo camera and a voice recorder, so this helped us get closer to what is a complex situation and try to get to know these people. The process was all about reaching reciprocal understanding: we needed to get to know them, of course, but it is also true that they needed to get to know us as well. Aside from cultural issues, our different languages caused the biggest problems. But slowly but surely, we reached a certain level of understanding, helped by the fact that at that time I actually lived near the refugee center myself and so I could sometimes be of practical help, all the while building trust with them. All the projects I’ve done with refugees have been thanks to building genuine relationships, in the sense that I’ve always tried to see their side of things: what it means for them to be refugees; having documents proving their refugee status but finding themselves in a new country with nowhere to call home. And so, I ask myself: what does it mean to cross a desert, to face Libyans? What does it mean for women to be raped and abused, cross the sea in open boats, risk one’s life, and then find oneself here, homeless? How do they react? What everyday battles are they facing now?

Figure 2 - Shukri, A New Life (2010), Production Azul for Al Jazeera.

S- Earlier, you mentioned some documentary filmmakers you met while pursuing your master’s degree in England. Can you name anyone in particular that inspired your own documentary work?

R- Well, to name a few: Molly Dineen and Kim Longinotto are two who inspired me most from a female point of view and helped set the direction for my work, especially as a woman in a field (cinema) where men still predominate. Both were great examples, especially if we consider that in Italy at the time there were hardly any women making documentaries. As a student of cinema at the time, I watched and studied a lot of “cult” films, and I believe that Neorealism films and the French Nouvelle Vague inspired me as well. Two other important points of reference for me were Werner Herzog and Krzysztof Kieślowski. They studied human themes from a psychological perspective. There are so many filmmakers, of course, and I think it’s wonderful to be able to pick up tips from each one.

S- You mentioned two women as being role models for you. What is your opinion on the role of women in the world of filmmaking? How much has being a woman influenced your work? Is it correct to say that your filmmaking expresses a “female point of view”?

R- I don’t believe there’s such a thing as a female or a male point of view, per se. I believe that you can talk about a very subjective point of view or a cultural point of view, in the sense that your outlook is influenced by the training you receive. Your training causes you to develop your own particular way of approaching people. In my films, I represent both men and women, and I usually work with both sexes; for me, there is no difference. Any differences are more around people’s personalities and ways of working. For example, I remember doing a piece of research where I had a male assistant. Even though I was the one asking the questions, the people I was interviewing always addressed their answers to him, assuming that he was the filmmaker rather than me. The poor guy kept telling them, “No, she’s the filmmaker, I’m just helping,” but in some environments, it’s so uncommon to see a man as a woman’s assistant that it’s just difficult for people to grasp. It was fun working with the guy, but in the end, I decided it was best to go it alone if I was going to create any strong connection with the interviewees. Also, being a female documentarian isn’t always easy from the financial point of view, especially when you have kids. In the film world, there’s little support, no maternity cover, and it’s difficult to find nursery schools. So, especially starting out, it’s a difficult job unless your family supports you. This is an issue that needs much more attention. Why, in 2020, do so many women still have to choose between work and motherhood? Some journalists asked me how it is possible to combine this work with maternity, but why don’t men have this problem? Nobody says to a man, “You’re a father, so how can you be a filmmaker?!”. And let’s look at film schools for a moment. I attended classes and seminars where the teachers were almost all men, although the student population was mixed. What kind of example are we setting for young women? Why should they have all these obstacles to overcome?

S- Does a “women’s cinema” exist?

R- I think this is more a political than a thematic question. For example, some research done by DEA (Donne e Audiovisivo) has shown that women have fewer chances than men of landing important roles in filmmaking. Rather than filmmakers or producers, women are often relegated to auxiliary roles, such as assistants and secretaries, and we should be asking ourselves why. So, it’s more difficult for women to get into this world. I believe that any event that encourages the presentation or production of women’s work is both important and useful. For this reason, I find the Women Film Festival really interesting, not only because all the films are made by women, but also because they show the great results that women can deliver, in spite of the challenges they face. A major obstacle is often lack of funding or having to work with reduced or smaller budgets as compared with their male counterparts.

S- Continuing on the “female” theme, could we talk about Ninna Nanna Prigioniera (2016), your documentary on motherhood in Italian prisons? How did this project come about?

R- It was completely by chance, actually, from a chance encounter. In fact, after my son was born, I took a course on child massage, and the nursery where the course took place happened to be near Turin prison. I can’t remember why, but the instructors mentioned that they regularly arranged activities for prisoners’ children. That was an eye-opener for me because I hadn’t known that the Italian legal system guarantees the maintenance of the mother-child relationship, especially during the first three years of the child’s life, after which women were given a choice whether or not to keep their children[1]. It seems an extremely forward-thinking law, respectful of the human rights both of mother and child. But, as a mother, I asked myself how you could possibly raise a child in prison because I imagined – even unfamiliar as I am with the prison world – that the difficulties would be enormous. The idea really touched me, and being a mother myself, I was curious, I wanted to learn more. This was something everybody should know about. Once again, the process was very long: I first did some research on the “outside,” talking to teachers and prison staff, and then I was allowed to go inside the prison to film. My focus was to shed light on the main things that were being done to protect these mother-child relationships. For example, soon after my film came out, a place called ICAM (Istituto di Custodia Attenuata per Madri) was built. It’s a completely different kind of place from the prison we see in the film. There are no bars, and everything is focused on children: it’s a good first step, but there’s so much more to be done. I think that my next project will be about ICAM, a window into what older children experience. Unlike the children in Ninna Nanna Prigioniera, these will be able to describe their personal experiences for themselves. My aim is to produce a film from their point of view.

S- How did you feel when you were making this documentary?

R- In some ways, my reflections are “inside” the film, but well, I would turn the question back to you. How did you feel watching it? What were your thoughts and impressions after watching the film?

S- What I noticed was how it really does make us see things through the children’s eyes, especially little Lolita’s. Focusing on the children certainly helps us to understand how they feel.

R- Yes, that was my objective: to tell the mothers’ story, obviously, and especially the children’s. And because they can’t talk very well at that age yet, I decided I would follow them around, putting the camera at their level so I could show the world as they see it. In effect, sitting on the ground to play with them, I realized that the world is different if you look at it from a different height; you see things in a different way, you give more attention to details like the uniform, the gun, the bars. Everything looks much bigger to them. And so, talking with the director of photography Stefania Bona, we decided to present the two different points of view. Whenever we were with adults, we filmed at their level, and when we were with children, we sat on the floor to try to capture things from their perspective. A child’s way of seeing a prison is very different: for them, it’s another kind of place altogether.

Figure 3 - Ninna nanna prigioniera (2016)

S- Your filmmaking style is very much about realism, working through the voices and gestures of your subjects. I was wondering, is there any specific reason that led you to adopt a “cinéma vérité” style over any other?

R- As I said earlier, I studied visual anthropology, and in the documentaries that I watched and analyzed, there were important examples that have definitely affected my choices since. Think of Rouch and MacDougall, all masters of observation. Their intention is not to tell stories using words, to give verbal descriptions of what’s going on, but rather to show the situation and to evoke the story through observations and scenes able to immerse the spectator as much as possible, even if just in a mediated way. So, I don’t want to say openly to the viewer: “Look, the situation is this, and this is what’s happening.” That’s what many Italian documentaries of the 1960s did: a voiceover explained what was exactly happening in the scene. But I try to build a cinematographic story - using images, sounds, locations, and so on, leading the audience to form their own opinion about what they see. Clearly, I’ve got my own particular point of view on this, but what I’d really like is for every viewer to get inside the film, really inside it, to really know what it’s talking about, and then have them reflect on it as compared with their own experiences. What a mother perceives when watching Ninna Nanna Prigioniera is different from what a young person perceives. I find interesting the real relationship that’s created between the viewer and the reality that I show. “Cinéma vérité” is a method that enables the viewer’s active participation in defining the content’s meaning, and precisely for this reason, it’s also more dangerous because there’s not just one message, but a series, all lived in different ways by the different viewers. I believe that this is what’s great about cinema, its greatest potential. Think about those films that transport you into a very different world -Rohrwacher or Garrone’s, for example- There is this idea, right? To become immersed in a world, hear the sounds, see through the protagonist’s eyes, and ask yourself some questions. In fact, it impressed me that in your question you used the phrase “I was wondering.” My goal is precisely to make the viewer see a different reality and, like me, to start asking questions. The great richness in every creative work is that we have to open up the world, to create dialogue, not just supply a user guide.

S- What you do in Libere (2017) is to create the space for dialogue between knowledge and understanding. You create a new way of seeing history, that of the Resistance, until now usually presented through the male gaze. Could you talk about this project now?

R- This project started with an idea from Paola Olivetti, the Director of Turin’s Archivio Nazionale Cinematografico della Resistenza. She knew she had in her archive a lot of precious interviews with women, most of whom have now died, which she wanted to see used in a film on the role of women in Italian Resistance. In the beginning, I was reticent, both because the Resistance seemed to me to be a topic consistently approached in much the same way, often a rhetorical way, and because this would be something completely new. In fact, I’ve always done research into contemporary situations, working with real people but here it would mean using an archive, exploring different sources of historical information. Having said that, at the same time I was rather intrigued because, after talking about prison and imprisonment, making a film about freedom and liberation instead seemed to be a positive move. I started watching all the important documentaries on the topic, like the one by Liliana Cavani (La donna nella Resistenza, 1965). I was also watching other short and lesser-known documentaries in Paola Olivetti’s archive— made using the same interviews I was going to be using later—and I read, I read a lot. There was Ada Gobetti’s Diario partigiano and the one by Bianca Guidetti Serra… There turned out to be a huge amount of published material available. Although this would be different from my other projects, the process would basically be the same: to try to understand the situation from the characters’ point of view, in this case, women’s. I simply asked myself, “how did they really live this story?” and I proceeded from there. Of course, with people who are still alive, research can be done via dialogue, while here I was going to be using written sources and interviews recorded by other people. So, I listened to them carefully, I read the transcripts, and I noticed that there were entire parts of interviews that had never been used: philosophical, political passages unveiling what political participation had really meant for these women. And I saw myself in those parts, starting a dialogue and the desire to realize a project that was not rhetorical, a work that did not bear with the usual pattern in which characters are a sort of heroes that do incredible things. Listening and reading to these interviews, for the first time, I felt I was witnessing “another” history, not just some kind of history-by-numbers, but one comprising real people, young people at that: some of these women were just fourteen or fifteen years old when they made their choices, and I wondered what I’d have done had I been in their shoes. So, again in my films, I always stick to the same process, to the desire to describe these figures not as heroes, but as ordinary people living in extraordinary times, making decisions and facing risks and challenges requiring extreme courage. Then, I wondered: why, still today, are partisan women so often represented as housewives in conferences or debates? Or as mothers, helpers, support systems? It’s not right; why not tell the truth? Isn’t it time to abandon the Italian rhetoric that still, even in 2020, refuses to recognize and accept that women can fight just like men? In my films, the partisans featured were girls who made a particular ideological choice, who learned to use guns, who fought, who made careful, responsible choices, and who wouldn’t have had it any other way. There were mothers among them, for sure, but there were also other women, young girls: those that took part in the Resistance because they chose to: they chose to fight. It seems to me that this idea still scares us, the idea that a woman has the right and the power to choose and act in her personal life. For this reason, I decided to select the passages that seemed not to tell very much, and that could add an important element to the few studies, like Bruzzone and Farina’s La Resistenza Taciuta[2], which investigate and reflect on this theme.

S- During the documentary, we see none of the subject’s faces, except in the closing photographs. We only ever hear their voices and the words they say. Why is that?

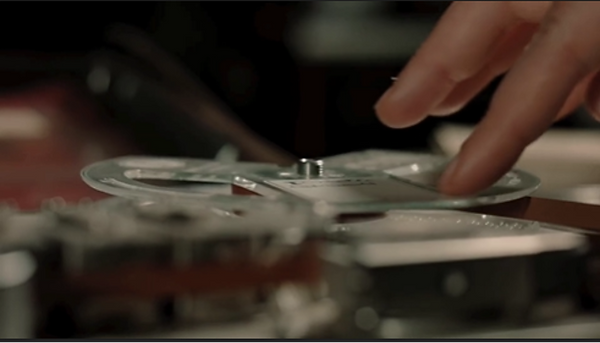

R- My idea of not showing their faces is primarily linked to my work around identifying with the stories we hear. But I should also say that there were also some technical problems. Maintaining good cinematographic quality was difficult because the materials were all in analog format and filmed more than twenty years earlier. However, my decision not toshow the faces was mainly the result of the feelings and the thoughts that I had when watching the interviews and reading through the archive material. In fact, while reading, I found myself imagining these girls - the moment they made their choices, their lives - and the simplicity with which they said things like “when I was thirteen, I went to work on a factory”- and I visualized them in the historical period that I was describing. Mine was an imaginative work, which found substance in the voices and words and not from videos because those interviews only showed elderly women telling stories about the past, and that, in this way, would remove me from the reality that I was trying to understand. So, seeing old people reminiscing only makes for a somewhat rhetorical discussion, like saying, “it was another time, it happened in the past. I’m old. I can tell you now.” On the other hand, I was interested in what the young girls had been thinking at the time, how they’d felt actually being partisans, not how they felt later in life. The only way I found of achieving this was to avoid showing the women’s faces. It was a long, complex work of evocation to recreate the circumstances of the young women’s lives. With the help of all the archivists and the editor who worked with me in the project, we looked long and hard for visual materials that could portray them in action, that would show them at the exact age they were when they made their commitment. This is important to emphasize because, for them, joining the Resistance was both a political choice -working for Italy’s liberation from Nazism and Fascism- and a bid to free women from an old patriarchal system.

Figure 4 - Libere (2017), produced by ANCR Archivio Nazionale Cinematografico della Resistenza and AZUL

S- Does this perhaps explain why your documentary starts by talking about the Resistance, and then moves to the Post-War period and its legacy of women’s suffrage?

R- Yes, because if you listen to what Bianca Guidetti Serra says, you see the positive evolution that’s taken place: the improvements in the system, the changes that have come about because of the fight those women put up. Showing the continuation between past and present was necessary because we are still questioning a world that is still more difficult for women than men. The answers are deeply rooted in history, and so we must study it more. Talking about the past is fundamental to understanding the present. This is why in making Libere I was continually pruning, just selecting everything that would help me not only present these different issues but also point forward to the present day. I wanted to do things differently, leaving behind the usual past works, which for the most part, were made by men who told history from their point of view. History often unfolds relative to the kinds of questions we ask, so I wanted to show history through answers to female questions, from the point of view of the women who themselves fought in the Resistance.

S- Yours is a story told through the archivist’s hands, shot while she was working on historical sources. It seems to me an original choice.

R– When I started exploring the archive, I quickly realized that it was pretty much an uncharted treasure chest. It contained a lot of valuable material, as yet unseen, including newspaper cuttings and rare photographs. It appeared to me to be a world at risk of disappearing due to a shortage of funding. And therein lies a whole new political discussion: this material needs to be preserved for posterity because, when it’s gone, there won’t be any more where that came from, and a piece of history will be lost forever. Ada Gobetti talked about the need for a researcher to study the Resistance, and that impressed me. In fact, I decided to include the clip of her saying so, at the opening of my film, because I had personally felt called to the task. With its footage showing the hands of the archivist, my documentary is an answer to her plea. It was a way to show the archives’ existence to illustrate how and where my research was carried out and how important it is that such archives exist. Have you seen the color photographs? Those, too, are from the archives. We should be asking here as well, why have they never been seen before? They are an important part of the history of humanity, a precious legacy to be treasured.

Figure 5 - Libere (2017)

S- In retrospect, many partisans regarded women's participation in the Resistance as the “beginning of women’s emancipation.” Would you say that they had an influence on the present and contributed to making the image of women what it is today?

R- Absolutely. The women in the interviews lived in a social structure still very much reminiscent of the 1800s. As they say, it’s thanks to women in the Resistance that the movement towards female emancipation was birthed. Think about women’s right to vote. It came about because of them, their participation, their demands. As for kindergartens and the welfare system—all these demands came from women who’d lived through those wartime experiences, from the connection that they had with people. Think of Teresa Noce and Nilde Iotti, who both went on to become elected members of Parliament. Remember how strongly they fought for change. They were just two of the many women Resistance fighters, to whom we can never be grateful enough.

[1] The reference here is to the Italian Law 62/2011, approved by the Italian Parliament to protect the relationship between women prisoners and their minor children:

[2] Anna Maria Bruzzone and Rachele Farina, La Resistenza taciuta. Dodici vite di partigiane piemontesi (Torino: Bollati Boringhieri, 1976).

To cite this interview, please use this reference: Raimondi, Silvia (2021) "A Conversation with Rossella Schillaci " Gynocine Project, Barbara Zecchi, ed. www.gynocine.com